Introduction

Mussels are among the many invertebrates under the Phylum Mollusca. Their wide distribution in the coastal areas of the Indo-Pacific region makes them the most easily gathered seafood organisms, contributing a significant percentage to the world marine bivalve production. In the Philippines, approximately 12,000 MT of mussels were produced in 1987. This amount consisted only of farmed green mussel.

Being a filter-feeder of phytoplankton and detritus, it is considered the most efficient converter of nutrients and organic matter, produced by marine organisms in the aquatic environment, into palatable and nutritious animal protein. Its very short food chain (one link only), sturdy nature, fast growth rate and rare occurrence of catastrophic mass mortalities caused by parasitic micro-organisms, makes it possible to produce large quantities at a very reasonable price. Mussel culture is the most productive form of saltwater aquaculture and its proliferation is virtually a certainty

Mussel farming does not require highly sophisticated techniques compared to other aquaculture technologies. Even un-skilled laborers, men, women, and minors can be employed in the preparation of spat collectors as well as harvesting. Locally available materials can be used, hence minimum capital investment is required. The mussel harvest can be marketed locally and with good prospects for export.

Success in mussel farming, however, depends in providing some basic requirements to the bivalve such as: reasonable amount of sheltering of the culture areas, good seawater quality, and sufficient food in the form of planktonic organisms. These pre-requisites are found in some coastal waters, hence locating ideal sites for mussel cultivation is essential.

3.1.1 Site location

In prospecting sites for mussel cultivation, well-protected or sheltered coves and bays are preferred than open un-protected areas. Sites affected by strong wind and big waves could damage the stock and culture materials and, therefore, must be avoided. Another important consideration is the presence of natural mussel spatfall.

Areas serving as catchment basins for excessive flood waters, during heavy rains, should not be selected. Flood waters would instantly change the temperature and salinity of the seawater, which is detrimental to the mussel.

Sites accessible by land or water transportation are preferred so that culture materials and harvests can be transported easily.

3.1.2. Water quality

Areas rich in plankton, usually greenish in color, should be selected. Water should be clean and free from pollution. Sites near densely populated areas should not be selected in order to avoid domestic pollution. In addition, the culture areas should be far from dumping activities of industrial wastes and agricultural pesticides and herbicides.

Waters too rich in nutrients, which may cause dinoflagellate blooms and render the mussels temporarily dangerous for human consumption, causing either gastro-intestinal troubles or sometimes paralytic poisoning, should be avoided.

Water physio-chemical parameters are also important factors to be considered. The area selected should have a water temperature ranging from 27–30 °C, which is the optimum range required for mussel growth. Water salinity of 27–35 ppt is ideal. A water current of 17–25 cm per second during flood tide and 25–35 cm per second at ebb-tide should be observed.

Favourable water depth for culture is 2 m and above, both for spat collection and cultivation.

3.3.3. Bottom type

Bottom consisting of a mixture of sand and mud has been observed to give better yields of mussel than firm ones. It also provides less effort in driving the stakes into the bottom. Shifting bottoms must be avoided.

3.2 Cultured mussel species

Among the mussels proliferating in the coastal areas of the tropical zone, the green mussel, perna viridis (mytilus smaragdinus), called tahong in the Philippines, is the only species farmed commercially. In the temperate zone, it is the blue mussel, Mytilus edulis, as this species can grow at low seawater temperatures.

3.3 Culture methods

Mussel culture, as practiced in many countries, is carried out by using a variety of culture methods based on the prevailing hydrographical, social and economic conditions.

3.3.1. Bottom culture

Bottom culture as the name implies is growing mussels directly on the bottom (Fig. 1). In this culture system a firm bottom is required with adequate tidal flow to prevent silt deposition, removal of excreta, and to provide sufficient oxygen for the cultured animals. This method requires a minimum investment. Disadvantages, however, of this type of culture is the heavy predation by oyster drills, starfish, crabs, etc. Also, siltation, poor growth and relatively low yields per unit culture area.

3.3.2. Intertidal and shallow water culture

Rack culture.

This is an off-bottom type of mussel culture. Rack culture is predominantly practiced in the Philippines and Italy where sea bottom is usually soft and muddy, and tidal range is narrow. The process involves setting of artificial collectors on poles or horizontal structures built over or near natural spawning grounds of the shellfish. In the Philippines, this is called the hanging method of mussel farming. The different variations used are as follows:

Hanging method. The process starts with the preparation of the spat collectors or cultches. Nylon ropes or strings, No. 4, are threaded with coco fibre supported by bamboo pegs or empty oyster shells at 10 cm intervals. These collectors are hung on horizontal bamboo poles at 0.5 m apart. A piece of steel or stone is attached at the end of the rope to prevent the collector to float to the surface. Setting of collectors is timed with the spawning season of the mussels. Spats collected are allowed to grow on the collectors until marketable size.

Stake (tulos) method. The stake method is midway between the rack and bottom methods. Bamboo poles, 4–6 m in length are staked firmly at the bottom in rows, 0.5–1 m apart during low tide in areas about 3.0 m deep and above (Fig. 3). In areas where water current is strong, bamboo poles are kept in place by nailing long horizontal bamboo supports between rows. Since mussels need to be submerged at all times, it is not necessary that the tip of the poles protrude above the low water level after staking. However, boundary poles should extend above the high water level. In staking, enough space between plots is allowed for the passage of the farmer's banca during maintenance.

Collected spats are allowed to grow in-situ until marketable size, 5–10 cm after 6–10 months. It has been observed, that about 2,000–3,000 seeds attach on 1 metre of stake, 1–2 m below low water level.

Tray culture. Tray culture of mussels is limited to detached clusters of mussels. Bamboo or metal trays, 1.5 m × 1 m × 15 cm sidings are used. The tray is either hang between poles of the hanging or stake methods or suspended on four bamboo posts.

Wig-wam culture. The wig-wam method requires a central bamboo pole serving as the pivot from which 8 full-length bamboo poles are made to radiate by firmly staking the butt ends into the bottom and nailing the ends to the central pole, in a wigwam fashion. The stakes are driven 1.5 m apart and 2 m away from the pivot. To further support the structure, horizontal bamboo braces are nailed to the outside frame above the low tide mark. Spats settle on the bamboos and are allowed to grow to the marketable size in 8–10 months.

Rope-web culture. The rope-web method of mussel culture was first tried in Sapian Bay, Capiz, in 1975 by a private company. It is an expensive type of culture utilizing synthetic nylon ropes, 12 mm in diameter. The ropes are made into webs tied vertically to bamboo poles. A web consists of two parallel ropes with a length of 5 m each and positioned 2 m apart. They are connected to each other by a 40 m long rope tied or fastened in a zigzag fashion at an interval of 40 cm between knots along each of the parallel ropes (Fig. 6). Bamboo pegs, 20 cm in length and 1 cm width are inserted into the rope at 40 cm interval to prevent sliding of the crop as it grows bigger.

4.0 Mussel transplantation to new site

Transplantation of young mussels from natural spawning grounds to sites with favourable conditions for growth is practiced in numerous countries as mentioned earlier. In the Philippines, however, mussel transplantation to new sites is being encouraged to develop new areas for mussel culture, due to various reasons. Major reasons are: rampant pollution of some existing mussel areas, urbanization growth near mussel farms and competitive use of lands.

Mussels to be transplanted could be breeders or young adults. Important points to be considered are: Conditions from natural spawning areas must be almost similar to the new area, mussels on original collectors showed better survival than those detached, and in transporting the mussel avoid being exposed to heat and freshwater.

5.0 Harvesting procedure

Harvesters should be aware of the stress caused during the harvesting process. In harvesting mussels special care is needed. Pulling them or using a dull scraper may tear the byssal thread. This will result in loss of moisture after harvest or cause physical damage causing early death of the bivalve. The right procedure is to cut the byssal thread and leave it intact to the body. Exposure to sun, bagging and transport also increases the stress of the mussels.

7.0 Economic aspects (the figures and amounts below maybe outdated and just an estimated value)

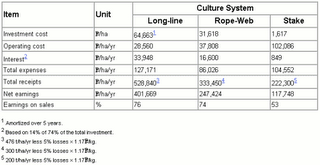

TABLE 1. Project costs, income from mussel farming at Samar by long-line, rope-web and stake culture systems.

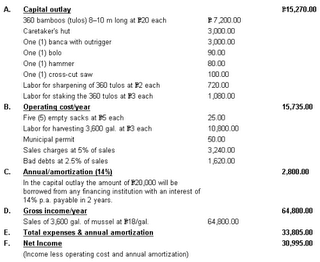

TABLE 2. Cost-benefit ratio for a 300 sq. m. area of mussel stake culture.

Processing

The term primary processing is applied to the component of mussel production to make it ready to the live, fresh market. Secondary processing is applied to frozen, canned or cooked mussels.

Depending on the goals and focus of the growers, those who get involved in the promotion of their crops enjoy a much greater return for their product than those who don't.

It is important to remember that until somebody consumes what you grow, you are just spinning your wheels. As the production of cultured mussels continues to expand, consumption must increase also. Controlling quality is one key to that growth.

Mussel growers have a number of options for which to choose when deciding on socking material and methods. It's important to consider the region and specifics of the site when making the choice, with an eye toward achieving a profitable seed conversion ratio.

picture from www.coconutstudio.com

Related Links:

Agri Business

1 comment:

thanks. it really helps.

Post a Comment